Alcohol The first step to integrated pest management of Varroa mites is testing your hives about once a month to monitor your mite levels so that you can treat at the appropriate time with the appropriate treatment. There are 2 validated testing methods for Varroa mites: 1) the powdered sugar roll, and 2) the alcohol wash. Of the two, the alcohol wash is easier and more accurate, but it does kill the tested bees (although properly done, the powdered sugar roll will also probably kill some bees). Both tests require 300 bees (½ a cup) collected from the brood chamber. Sticky boards are often advertised as a non-invasive way to test for Varroa mites, but these are not an accurate or useful way to test your mite levels. Testing is crucial to mite control because treating at the wrong time can be harmful to your bees and create resistance in the mites. There is an app called MiteCheck to help guide you in testing your bees for Varroa mites. Biters Think of IPM as a pyramid. At the bottom are preventative techniques and at the top are interventions/treatments. The base of preventative techniques is termed cultural. These include culling old comb (Varroa prefer old comb), introducing mite-resistant bee stock into your apiary such as Purdue Ankle-Biters, VSH (Varroa Sensitive Hygienic) or Saskatraz, and breaking the brood cycle (because the mites reproduce in the brood). Some models will also list small-cell comb as a cultural control, but recent studies have proven this is not an effective control of Varroa mites. Capture Next are physical or mechanical techniques. These include drone board removal or drone-trapping (which physically removes mites from the hive), screened bottom boards (which may prevent mites groomed from adult bees from crawling back on bees), and new products which heat the hives to temperatures at which mites cannot live. Some models will also list powdered sugar as a physical control of Varroa mites, but scientific studies have shown that the periodic application of powdered sugar by sprinkling it into hives is ineffective in controlling Varroa mites. More Information: https://pollinator.cals.cornell.edu/sites/pollinator.cals.cornell.edu/files/shared/documents/2020%20IPM%20for%20Varroa%20Mite%20Control.pdf

0 Comments

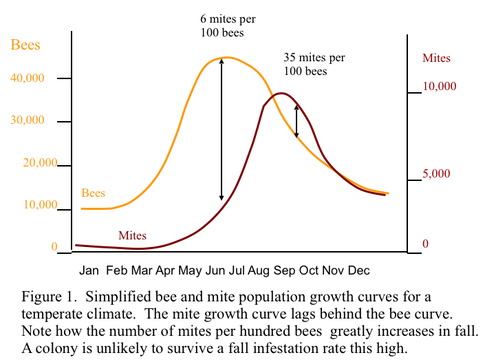

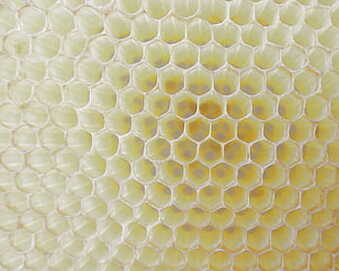

Copyright Randy Oliver, Scientific Beekeeping, 2006 Copyright Randy Oliver, Scientific Beekeeping, 2006 Accelerated Varroa mites breed exponentially. This means that an untreated, unmanaged hive with one mite in the spring will have thousands of mites by the fall. To make matters worse, the mite population of the hive is peaking just as the adult bee population of the hive is dwindling and just as special winter bees are being made to try to ensure the survival of the hive through the winter. The physical and physiological damage that the mites cause means that even if the hive technically survives to winter, the winter bees of the infected hive will likely be small and weaker than those of a healthy hive and the colony will not survive the winter. Booming One thing that sounds counterintuitive when it comes to Varroa mites is that big, booming colonies are more affected by mites than smaller, weaker colonies. This is because the mites breed inside the brood and a large hive with tons of brood will also therefore have a much higher mite load. Smaller colonies don’t have as much brood for the mites to “hide” in and breed in, and adult mites on adult bees may be groomed off by other bees. Unfortunately for beekeepers, it is often their largest, most “successful” hives that succumb to Varroa mites. Capped Varroa mites reproduce inside the capped brood cells of honey bees. The adult females can sense when a cell is about to be capped and jump into the cell and hide under the bee larva until the cell is capped. When the larva begins to pupate, the foundress mite feeds on the pupa and begins to lay her eggs. The first egg is always a male and the subsequent eggs are all females. When the eggs hatch the female mites will breed with the male mite and when the weakened adult bee emerges from the cell, the mated females (including the foundress) will escape and find adult bees to attach to. Varroa mites prefer to reproduce in drone brood cells because drones take longer to mature and therefore more of the mite eggs will have time to hatch and mate releasing more mature, adult mites on average. More Information: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k6y9FqNw6y8  All All honey bee colonies, except those which are extremely isolated with no other hives in at least a 12-mile radius, are affected by Varroa mites or subject to infection through visiting the same flowers as infected bees, robbing hives infected by Varroa, “drift” (bees coming home to the wrong hive) of bees from infected hives, and most importantly from hives that have become “Varroa bombs.” A Varroa bomb is a colony that has become so infested with Varroa mites, that the remaining live bees all abscond (leave in mass) from the hive and fly off in every direction to find a new hive. These bees spread the mite infection far and wide and can cause a rapid and fatal increase in Varroa mites, even in a previously uninfected hive. Big Beekeeping in North America is now much more difficult due to this insidious parasite. Large for mite, Varroa is still nearly impossible to spot on a honey bee because it often hides between the plates of exoskeleton on the bee’s abdomen where it punches a hole in the bee’s cuticle and feeds on the adult bee’s fat bodies. Varroa also damages bee pupae when it reproduces inside capped brood cells and feeds off the developing brood. As if this was not enough damage, Varroa mites have also been shown to spread bee viruses such as Deformed Wing Virus (DWV) and activate bee viruses already present in a colony. Cerana In 1985 beekeeping in North America was forever changed by the introduction of the Varroa destructor mite from Asia where it is a parasite of the Asian honey bee, Apis cerana. Apis cerana, having evolved alongside the Varroa mite, has developed multiple strategies for dealing with it. Unfortunately, Apis mellifera, the Western honey bee and the bee kept by almost all beekeepers in North America, did not evolve with this mite, and has had little time to adapt to Varroa destructor. More Information: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0135103  Aims Many beekeepers split their hives in the spring. This is done for several reasons: 1) To create an artificial swarm to prevent swarming, 2) To increase the number of hives, 3) To create a break in the brood cycle to help control Varroa mites, 4) To encourage the bees to raise a new, young queen, 5) To make money by selling nucs or miniature hives. 6) To make smaller hives with less bees to increase the chances of finding the queen and dispatching her to introduce a new queen and new genetics. Basic There are 2 main types of splits. With the first type, finding the queen is not necessary. With the second type, you must find the queen. The most common 1st type is called a “walk-away” split. In this split you divide the hive evenly between two boxes making sure that each has an equal number of bees as well as frames of pollen, nectar, brood, and especially at least one with eggs present. One of the boxes gets left in the location of the old hive and one gets moved to a new location and some grass or other debris placed in or over the entrance to allow bees to acclimatize to the new location. Then the beekeeper “walks away” for 4-7 days. After that time, one of the hives will have eggs and you know that’s where the queen ended up without having to find her. The other hive will have queen cells as the bees are queenless and need to make a new queen. Conditions When is the best time to make splits? In order to have a chance at a successful split, there must be enough mature drones in your area to mate with the new queen. In Southeast Michigan, this is typically around the time of the dandelion bloom or May 1st, but the best way to determine the proper time is to check your drone brood. A sign that you will have mature drones by the time your new queen is ready to mate is when the drone pupae have purple eyes. Also, you will want the weather to be above freezing at night so that the smaller split hives will be able to keep their brood warm. More Information: https://www.honeyflow.com/blogs/beekeeping-basics/spring-split  Adverse Even though it can be a sign of a strong, healthy colony, swarming can be bad for your colonies. Not only do you lose your queen and about 60% of your bees, but roughly 20% of the time, the remaining weakened colony fails to produce a well-mated new queen to replace her and may be doomed if you don’t notice and install a new queen soon enough. The bees who leave in the swarm also fill their honey stomachs with honey from the hive so they can start building wax at their new home and take pollen for the new brood. This means less resources for the remaining bees and beekeeper. Breeding Swarming is a natural process for a honey bee colony. All colonies want to swarm because this is the way the colony reproduces as a superorganism. That being said, allowing your colonies to swarm, especially if you live in an urban or suburban environment, is not responsible beekeeping. Think of it as not spaying or neutering your dog and then expecting your neighbor to take care of all the puppies, or worse, no one taking care of the puppies and them all dying of disease and starvation. What I mean by this analogy is that swarms may take up residence in your neighbor’s siding or grill or attic where they do damage and aren’t welcome, also most swarms die (only 1 in 6 survives) because they cannot find a good new home and build up enough stores to survive a Northern winter with no beekeeper to care for them. Also, please remember that honey bees are not native to North America, so releasing them into the wild isn't good or nice for our native bee populations. Even though swarms aren’t good and get a bad reputation for being sting crazy, bees who are swarming are actually very docile because they have no home to defend. Crowding Spring, when flowers are blooming and nectar is abundant is swarm season in Michigan. The incoming nectar, warm weather, the queen running out of space to lay eggs, crowding of the hive with new bees, and the related decrease in queen pheromone are all cues for the bees to swarm. Space issues in the hive are something the beekeeper can control for by adding boxes of drawn comb. One sign your hive is getting too crowded is backfilling of the brood nest with nectar or bees storing nectar in the middle of the brood chamber leaving the queen nowhere to lay her eggs. If you see queen cells, your hive will swarm or has already swarmed (i.e. it’s too late). Most beekeepers create an artificial swarm by splitting their hives in the spring to prevent their colonies from swarming on their own. More Information: https://www.perfectbee.com/a-healthy-beehive/inspecting-your-hive/recognizing-and-avoiding-swarms  Adolescent Bees need three things to produce comb: 1) Lots of worker bees of the proper age (adolescent bees that have just finished their nurse bee duties), 2) Warm weather/proper time of year (bees will not produce wax in cold weather or during a dearth or when they are storing honey for winter), 3) Lots of fresh nectar or sugar syrup (it takes roughly 7lbs of honey to produce 1lb of wax)! Bees produce tiny flakes of wax from glands on their abdomens. Bigger, well-fed colonies with more bees will produce more wax. Build Bees need someplace to put the wax and build their comb. Most beekeepers place foundation inside their frames to aid the bees in building sturdy, straight comb with cells of the proper size. Foundation is a 2-dimensional template with cell outlines stamped on it. It can be made of wax or wax-coated plastic. When you reuse plastic frames, you may have to recoat them with wax. Some beekeepers use foundationless frames. While bees will build wax in these frames, the comb will be delicate, hard to handle, and impossible to extract without destroying it. Also, it will be difficult to prevent crooked comb or cross-comb (sideways comb connecting 2 frames together) which will ruin the comb when the frames are pulled apart. Crucial Honey comb or wax comb is incredibly important to a honey bee colony and a fundamental resource for the beekeeper. Bees raise brood and store food in the comb, and cluster and communicate on the comb. A colony cannot function without drawn comb. Drawn comb refers to 3-dimensional beeswax with hexagonal cells. Comb doesn’t last forever and old, dirty, dark comb should be rotated out of the hive every 3-5 years because it is full of dirt, debris, and absorbed chemicals like pesticides. More Information: https://www.honeybeesuite.com/the-conditions-necessary-for-comb-building/  Age There is a big difference between the physiology of honey bee workers in the summer and those who survive the winter. Summer bees only have a lifespan of around 5-6 weeks while winter bees can live up to 3-6 months! This is very important since brood production basically stops in the winter. Winter bees can even be considered a different caste of honey bee! Bodies (Fat) The main reason for this difference is instead of running themselves ragged (literally, older summer foragers have tattered wings) foraging for food stores to feed the colony throughout the winter, winter bees conserve their energy and have larger fat bodies to help them survive the cold (or nectar dearth, depending on the climate). These fat bodies contain abundant vitellogenin which is a protein-rich substance that can take the place of pollen in the winter. Confined Winter bees spend their entire lives (except for the occasional cleansing flight) inside the hive caring for the queen, and in early spring will raise the brood that will inherit the colony and continue its growth in the coming warm months. More Information: https://www.honeybeesuite.com/what-are-winter-bees-and-what-do-they-do/  Angle When a forager returns from an abundant food source, she will regurgitate some of the nectar and pass it on to other foragers on the dance floor. Straight up is always the position of the sun on the dance floor, so if she then performs her waggle dance at an angle 60 degrees to the right of straight up, other foragers know that they will have to fly 60 degrees to the right of the position of the sun to find the nectar source. Since bees can see polarized light, they can still use the sun’s position for direction even on a cloudy day. Boogie There is a dance floor in every honey bee hive. It is located on the surface of the wax comb near the entrance of the hive. Foragers who have found a good source of nectar will perform a series of motions (dance) here to tell other foragers where to find this nectar source. Honey bees are one of the only animals other than humans who are able to tell another member of their species where something is without having to show it to them. Convey The waggle dance tells other bees not only how far away the food source is, but also in what direction. Distance is roughly determined by the duration of the dance. A longer dance indicates a greater distance from the hive. The direction another bee must fly to reach the nectar source is determined by the angle the bee dances relative to the position of the sun. More Information: https://bee-health.extension.org/dance-language-of-the-honey-bee/  Alteration The receiver bee takes nectar from the forager bee and transfers it mouth to mouth to other bees, adding an enzyme called invertase (sucrase) in the process which breaks the sucrose in the nectar down into fructose and glucose, and dehydrating the liquid down to roughly 18-20% water. The nectar is now honey and the bees will deposit it into a cell and cap it with wax. Sometimes the bees will store the nectar in cells before drying it out. Unlike with pollen, each nectar/honey cell is filled only with honey or nectar collected from the same species of plant. Barf Forager bees collect nectar by sucking it up with their proboscis into their honey stomachs (crops), and bring it back to the hive. When a nectar forager returns to the hive with a honey stomach full of nectar, she signals other bees to receive that nectar and fills the receiver bee’s honey stomach via trophallaxis or the regurgitated exchange of liquid. Carbohydrates Nectar is a sugary liquid excreted from the nectary of flowers to attract pollinators. It is the main source of carbohydrates for bees and also may contain very small amounts of vitamins, minerals, and other micronutrients. More Information: https://honeybee.org.au/education/wonderful-world-of-honey/how-bees-make-honey/  Anther Foraging bees get pollen all over their bodies as they collect it from the anther of the flower and store it in their corbicula or pollen basket located on their hindmost legs. They will also get some pollen on them when foraging for nectar in the flower. Tiny hairs all over the bee’s body and static electricity help to adhere the pollen grains to the bee. Since bees typically only forage from the same species of plant on each foraging trip (floral fidelity), they end up providing the plant with the valuable service of pollination by transferring the pollen from the anther (male organ) of one flower to the stigma (female organ) of another flower while foraging. Bread Pollen is the “sperm” of plants and is the honey bee’s source of protein, lipids, some vitamins and minerals, and micronutrients. The pollen is mainly consumed by bee brood and the nurse bees who produce protein-rich royal jelly from the hypopharyngeal glands in their heads. Pollen is made into bee bread in the hive by mixing it with honey and allowing some fermentation to occur. Making the fresh pollen into bee bread allows it to be stored for a longer period of time. Fresh pollen will get moldy and lose its nutritional value quickly. Bees prefer fresh pollen to old pollen and will “entomb” old, gross pollen with propolis and never go near it again. Frames of entombed pollen should be culled. Corbicula Bees will store the pollen from multiple different plant species together in the same cell. The pollen foragers empty their pollen baskets into the cell with their front legs and then pack the pollen down into the cell with their head. The pollen is normally stored right next to the brood or on frames close to the brood chamber. If the colony is suffering from a pollen dearth, the larvae will look dry and clear rather than plump and white and the liquid around them will also be clear instead of white. Some beekeepers feed dry pollen substitute or pollen patties (made from other protein sources like soy flour or skim milk) in the spring or during a pollen dearth. More Information: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN868 |

AuthorJen Haeger is a new master beekeeper and board member of A2B2. Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed