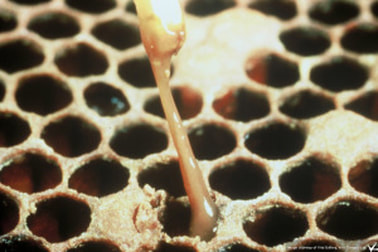

American Foulbrood rope test (Vita Bee Health) American Foulbrood rope test (Vita Bee Health) AFB American Foulbrood or AFB is a serious, highly contagious, and fatal bacterial disease in honey bees. It does not affect humans. The bacteria, Paenibacillus larvae, is fed to the bee brood as a spore from contaminated honey and then turns vegetative (reproductive) in the gut of the bee larva. This disease effects the bee brood typically after it has been capped, and instead of developing into a pupa and eventually an adult under the wax cap, the larva turns into a mass of bacterial goo containing millions to billions of spores. Less than 10 spores are needed to cause infection in a new larva. Burn Because this disease is so serious and contagious, infected hives must be quarantined and no equipment shared with any other hives. Though able to be controlled with antibiotics, the recommended treatment for a small operation is closing up the affected hive at night, digging a hole, placing the whole hive in the hole, burning it, and then burying the ashes. Some states REQUIRE you to do this. It may seem extreme, but the spores of AFB remain infectious for more than 80 years and are not destroyed through any common sterilization techniques. AFB is the main reason new beekeepers should not purchase old equipment, especially frames, from sources such as Craig’s List. Caramel Signs of AFB include a spotty brood pattern, caramel colored brood, sunken wax cappings often with holes in them, near black scales in brood cells that are impossible to remove, snotty/ropey larval goo, a foul or rotting smell, and a structure called a pupal tongue in brood cells (a thin, dark, pointy structure crossing the cell). While some of these signs can be seen with other brood diseases, the hard, black scales, larval goo ropes of at least 3.5cm, and pupal tongues are only seen with AFB. There are three tests for AFB: 1) Commercial Kit (similar to a COVID or pregnancy test), 2) Match Stick/Rope Test, 3) Holst Milk Test. More Information: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=caliX8JZJ2s

0 Comments

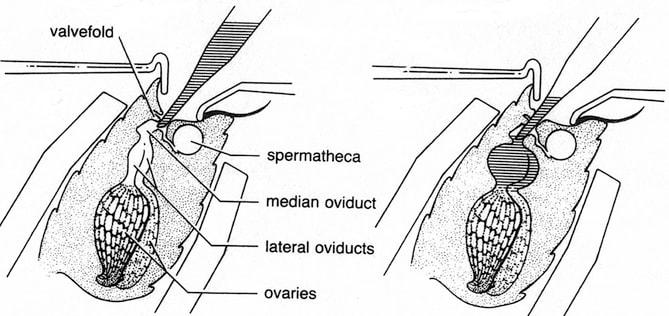

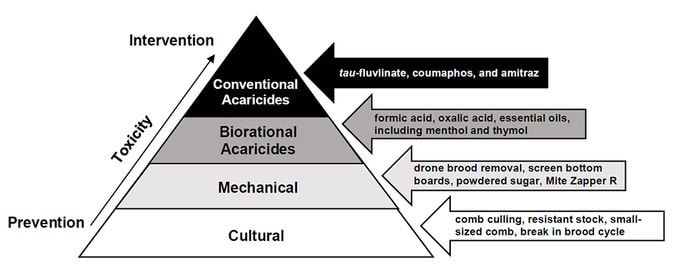

Assembly The standard Langstroth beehive is a wooden structure with several key parts. The first part is the bottom board which can be either solid wood or screened, a wooden frame with a screen in the middle to allow ventilation and a form of cultural mite control. The next part of the hive is one or more boxes filled with frames. Then comes the inner cover, a mostly flat piece of wood with a vent hole in the center. Finally, there is a telescoping outer cover that fits over the inner cover and a little bit of the top box to keep out rain and snow. The picture on the left also shows a hive stand which helps to raise a hive off the ground, but isn't a critical part of the hive assembly, and a queen excluder which goes between the brood box and the honey supers, but also isn't required. Boxes There are two lengths of boxes and three different heights of boxes. The two different lengths of boxes are 8-frame and 10-frame, being long enough to fit 8 frames or 10 frames respectively. The three different heights of boxes are deep, medium, and shallow. Deep boxes are typically used for the bee brood, mediums are sometimes used for bee brood, but more often for honey, and shallow boxes are pretty much exclusively used for honey. Because they are mainly used for honey storage, medium and shallow boxes are often referred to as honey supers, while deep boxes are also sometimes called brood boxes. Correct Frames are all the same length (the standard width of the boxes) and three different heights to fit the height of the box. Depending on the height of the frame (and which box they fit), frames are either deep, medium, or shallow frames. While a medium or shallow frame will fit in a deep box, it will not be as high as the box and will leave a gap between the bottom of the frame and the bottom board or the tops of the frames of the box beneath it. Bees will then spend a tremendous amount of energy adding comb to the bottom of the too-short frame to fill the gap, so generally a beekeeper wants to put the correct size frames in the correct boxes. More Information: https://www.uaex.uada.edu/farm-ranch/special-programs/beekeeping/uabeeblog/woodenware-guide.aspx Alternative A Warre hive is a vertical hive like the Langstroth hive with multiple boxes that may be heavy needing to be stacked. Unlike with the Langstroth hive where boxes are removed from the top of the hive stack, with the Warre, boxes are removed from the bottom of the stack. The believed benefits of a Warre hive are that it is “closer to nature” and requires less maintenance, but they only require less maintenance because they have much lower honey yields than a Langstroth hive. Normal maintenance for health, space, and disease are still required. It may be more difficult to find equipment and mentorship for a Warre hive and to test and treat the colony for diseases such as Varroa mite. Bench Mark I strongly recommend starting out with a Langstroth hive as a new beekeeper. Langstroth hive components are the easiest to find and often the most cost efficient. Also, most beekeeping courses, information, books, and internet videos are based on the Langstroth hive design. The main disadvantage of a Langstroth hive is that it can become quite tall and that the heavy boxes can be hard to lift and stack. This can be mitigated by splitting your hive in the spring and removing honey supers in a timely fashion. Climate The main advantage of a Kenyan Top Bar hive is that there is only one box and the colony grows horizontally so the beekeeper will not have to lift boxes off the stack. However, the one long box is quite bulky and heavy if it needs to be moved. Unfortunately, these hives are really meant for a more tropical climate, swarm frequently because the bees run out of space, and generally overwinter poorly because bees in a cluster prefer to move up instead of side to side to reach honey stores. They also either require special frames or are foundationless with very delicate comb that is difficult to handle or test for diseases like Varroa mites. Some people who make beeswax products prefer these hives because the bees need to make a lot of wax. More Information: https://www.honeybeesuite.com/in-praise-of-the-langstroth-hive/  Ancient Beekeeping really started in ancient times with honey hunting and humans harvesting the honey from hives in tree cavities. Traditional honey bee hives kept by the first beekeepers were either conical skeps made of straw or wicker plus mud or wax or cylinders of clay. The problem with these hives is that you have to destroy them to harvest the honey because the comb is fixed (not movable) inside the hive. Skeps are now illegal in some places because they foster poor management and promote disease. Bar The three most common modern beehive designs are the Langstroth hive, the Warre hive, and the Kenyan Top Bar hive. Of these, the Langstroth hive (invented by Rev. Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth) is by far the most common. One advantage of all of these hives is removable frames that help a beekeeper test for diseases such as Varroa mites and harvest honey without destroying the colony. Langstroth hives and Warre hives are vertical hives, but in Langstroth hives the honey supers go on top of the hive with the brood on the bottom, whereas in a Warre hive, the brood is on the top and the honey is on the bottom. Top Bar hives are horizontal hives with brood in the middle and honey on the edges. Curve There are probably hundreds of different hive designs out there, some designed for aesthetics (garden hives) and some for specific purposes like queen breeding (queen hotels). Still others are meant to simulate the natural habitat of honey bees (log hives). While others try to streamline aspects of beekeeping such as honey harvesting (Flow Hive). Starting out with a more common beehive design will probably help you overcome the steep learning curve in beekeeping and make it a more enjoyable experience. More Information: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-secret-to-the-modern-beehive-is-a-one-centimeter-air-gap-4427011/  Antimicrobial Propolis is a sticky substance made from the resin of certain trees. It is found inside honey bee hives coating the walls and sealing gaps. It not only helps to make the hive waterproof and airtight, but also is antimicrobial, acting as part of the honey bee super organism immune system. Some people take propolis orally (usually in a capsule or tincture) in the hopes that it will boost their immune system. Unfortunately, there is not much hard science to support this practice. Better Studies have shown that honey bee colonies that collect and use more propolis in their hives have lower incidence and better recovery from diseases like American Foulbrood (AFB), chalkbrood, and Nosema. Unfortunately, because it is sticky and makes it hard to inspect hives, beekeepers have been actively breeding out bee strains who collect and use lots of propolis. This, along with Varroa mites, may be one reason for the current high rate of colony loss. Cottonwood The trees that honey bees collect propolis from most often in Michigan are poplars and cottonwood trees. If bees do not have access to these trees, they may collect other sticky substances such as asphalt. Bees who collect propolis will only forage for propolis and never for pollen, water, or nectar. The resin is stored in the forager bee’s pollen basket, but when she returns to the hive, she will require another bee’s help to bite away the collected resin. More Information: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xsj8mB4KKZs  Artificial Insemination Diagram Honey Bee, Credit J. Harbo USDA Artificial Insemination Diagram Honey Bee, Credit J. Harbo USDA Assortment In the last post we discussed the different subspecies of Apis mellifera, the Western honey bee, the species of honey bee kept by beekeepers in the United States. From these subspecies, people have bred certain strains or stocks of bees. This selective breeding is usually done to preserve certain desirable traits, usually disease or mite resistance. The definitions of strains, stock, lines, and breeds of bees is a little murky and sometimes purebred subspecies of A. mellifera are also referred to as strains, stocks, lines, or breeds. Buckfast Some common honey bee stocks include: Buckfast, Saskatraz, Purdue Ankle-Biter (PAB), Varroa Sensitive Hygienic (VSH), feral chewers, and “survivor stock.” The Buckfast bee line is a subspecies of A. mellifera (A. m. buckfast) and was developed by a monk in England to fight the devastation wrought on English bees in the early 1900s by the tracheal mite. These are a combination of Italian bees and German bees. Saskatraz bees are from a breeding program in Saskatchewan, Canada whose primary goal was increased honey production (anecdotal reports say they are also resistant to Varroa mites). All the rest of the mentioned strains have been bred for either general disease (VSH) or Varroa mite resistance. “Survivor stock” are from overwintered colonies who survived Varroa mites with only rigorous IPM mite management and no chemical treatments. PABs and feral chewers are known for their increased grooming habits which include chewing the legs off of the adult mites and killing them. Control It is difficult to selectively breed bees because the queens mate away from the hive with 10-20 different drones from multiple colonies that are not their own. This maintains the genetic diversity which is normally better for keeping a colony healthy and prevents inbreeding. Unfortunately, this also means that most beekeepers have no control over the genetics their queens return with after a mating flight. Selective breeding programs either artificially inseminate the queens with sperm from drones with the desired genetic trait, or supersaturate the miles surrounding the queen’s hive with drones with the desired genetic trait. More Information: https://honeybeehealthcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Commercial_Beekeeping_062121.pdf (page 3)  Giant Honey Bees Giant Honey Bees Apis There are between 7 and 11 different species of honey bees. For example, Apis cerana, the Eastern or Asian honey bee is the original host for the Varroa mite, but is not found in North America. Apis dorsata, the giant honey bee, is also only found in South and Southeast Asia. Apis koschevnikovi inhabits Malaysian and Indonesian Borneo. Again, there are no native honey bees in North America, but the colonists brought over Apis mellifera, Western honey bees, and they have been present in North America ever since. Breeds Within the species Apis mellifera, there are 26 recognized subspecies. The most widely known subspecies is Apis mellifera scutellata, better known as the “Africanized” honey bee. Other common European subspecies of Apis mellifera include: Apis mellifera ligustica (Italian honey bee), A. mellifera carnica (Carniolan honey bee), A. m. mellifera (German black bee), A. m. caucasia (Caucasian honey bee), and A. m. artemisia (Russian honey bee). Characteristics Many bees in North America have become hybrids of these subspecies, so bees not obtained from a certified breeder will probably have mixed genetics from more than one of these subspecies. Generally, overwintered MI bees are considered “Michigan mutts.” However, some beekeepers choose to start with or maintain more pure lines of bees or hybrid bees that are a cross between certain subspecies based on the traits of those subspecies. For example, many people prefer Italians because of their calm temperament and increased honey production. Others prefer Russian bees for their reported Varroa mite resistance. Most beekeepers in the U.S. try to avoid keeping bees with Apis mellifera scutellata genetics because they tend to be super defensive bordering on aggressive, sting more frequently, swarm more often, and produce little honey. However, they are routinely kept by African beekeepers. More Information: https://bee-health.extension.org/subspecies-the-place-of-honey-bees-in-the-world/  America Many people get into beekeeping to “save the bees,” and honey bees have become a vital part of our agricultural system, pollinating crops such as almonds, blueberries, and apples. Unfortunately, honey bees are not native to North America, so keeping honey bees to “save the bees” is a lot like keeping backyard chickens to help with the plight of the Kirtland’s Warbler. Worse, when uneducated beekeepers fail to manage their colonies properly, they spread pests and diseases to our native bees, doing harm instead of good. But… I am NOT saying that we shouldn’t keep honey bees. I enjoy keeping bees, love honey, and have no intention of giving that up. However, what I am saying is that there are much better things to do to “save the bees” than to become a beekeeper. These include, but aren’t limited to, planting native forage, never planting ornamental flowers, limiting or stopping the use of pesticides in your yard, encouraging your local government to plant community gardens of native plants, cutting down on the amount of lawn you have and replacing it with native plants, supporting bee-friendly farms, planting bee-friendly trees, and donating to organizations who support pollinator education and conservation. Consider Consider also that honey bees often compete with native bees for our dwindling floral resources. Since the 1930s, the United States has lost a staggering 97% of wildflower meadows, leaving little forage for our native bees. Additionally, honey bees are often attracted to invasive plant species such as star thistle, proliferating this noxious weed. More Information: https://www.nwf.org/Home/Magazines/National-Wildlife/2021/June-July/Gardening/Honey-Bees  Assessment A hive inspection is a thorough examination and recording of the status of a hive including the contents of every frame. This is usually only done once a year. Most of the time beekeepers will be performing a hive check. For a typical hive check, the beekeeper is looking for 4 things: 1) Is the hive queenright?, 2) Does the hive have enough of the right kind food for the time of year?, 3) Does the hive have the proper amount of space for the time of year? 4) Are there any signs of disease or pest issues (i.e. doing a mite test)? Other more specific checks might be looking for things like queen cells or a virgin queen or if an introduced queen has been accepted, checking to see if a mite treatment was successful (i.e. retesting a hive for Varroa mites), finding and marking a new queen, or checking to see if two hives combined successfully. Before Before a beekeeper enters their apiary, they should have a plan for what they are going to do with each hive and the proper equipment to perform the checks, including some form of record keeping to keep track of what they intended to do and what they actually did. The beekeeper’s plan should include contingencies, for example, what to do if one of the hives is queenless or if one of the hives needs more space or if a Varroa mite test reveals the need to treat the whole apiary. This may also entail bringing extra equipment or mite treatments to the bee yard. C-shaped Checking if a hive is queenright doesn’t necessarily mean finding the queen. Often it is difficult for new beeks (beekeepers) to find an unmarked queen, but fortunately the presence of single eggs in the middle of the floor of a cell is a sign that a queen was present in the hive at least 3 days ago. Likewise, the presence of small, C-shaped larvae indicates a queen’s presence in the hive at least 6 days ago. Hives should have abundant pollen stores in the spring and summer for brood rearing and abundant honey stores in the fall for the winter. Bees generally require more space in the spring and summer less in the fall and winter. A careful inspection of the brood chamber and a Varroa mite check will often warn you of the presence of pests or pathogens. More Information: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CohtHUThEVc  Image modified by Morgan Roth, based on source material from the State of Hawaii Plant Industry Division Image modified by Morgan Roth, based on source material from the State of Hawaii Plant Industry Division Acids (& oils) The next level of the IPM pyramid is where intervention/treatment begins with what are termed “soft” chemicals. These are naturally occurring acids and essential oils commercially formulated for maximum efficacy against Varroa mites with minimal harm to your bees. “Soft” chemical acids include HopGuard 3, FormicPro, MiteAway Quick Strips, and Oxalic Acid. “Soft” essential oil treatments include formulations containing menthol and thymol like ApiLife Var. At the top of the pyramid are “hard” chemicals or conventional pesticides, to which Varroa mites have already developed resistance in some cases. These include amitraz (Taktic, Apivar), tau-fluvlinate, and coumaphos. Beware Any chemical treatment needs to be used with the utmost care with thought given to the temperature, time of year, whether or not honey supers are present, if there is brood present in the hive, and what protection needs to be worn by the beekeeper when administering the treatment. It is illegal to apply chemical treatments to your hive in a manner inconsistent with the instruction label. It is illegal to apply pesticides (including essential oils) to your hives that have not been approved for use as Varroa mite treatment in honey bees. When treating, it is best to treat all hives in an apiary at the same time. This prevents the mites from "hive-hopping" from the treated hive to an untreated hive. Cruel Do you know what doesn’t work as a treatment? Doing nothing, letting your bees “develop resistance” against Varroa, letting the “weak” bees die (this is animal cruelty), and creating Varroa bombs that infect your neighbor’s hives and the local native bee population. “Treatment-free” does not mean doing nothing. In fact, it is a rigorous system of integrated pest management that includes actively euthanizing mite-susceptible hives. For most new beekeepers, this is not a viable strategy for mite control. More Information: https://honeybeehealthcoalition.org/varroatool/ |

AuthorJen Haeger is a new master beekeeper and board member of A2B2. Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed