Absent? One of the most common problems beekeepers think they face is a colony that is queenless. I say “think” because sometimes a seemingly queenless colony isn’t actually queenless. Just understanding the biology behind a queen’s development will help determine if a hive is truly queenless. First, let me say that you don’t always have to see your queen when inspecting a hive. If you spot eggs (single eggs laid in the middle of the bottom of a worker-sized wax cell), then you had a queen in that hive at least 3 days ago. Similarly, if you see small, C-shaped larvae, then your hive had a queen at least 6 days ago. If you only spot big, fat larvae or capped brood cells, depending on the time of year (you may not see eggs in the fall), you may have a queen issue. Also, multiple eggs in cells or eggs laid on walls of the cells or drone brood sticking out of worker-sized cells may be an indication of a laying worker hive that has been queenless for at least 6 weeks. Brief The development cycle of a queen from an egg to an adult is the quickest of all the honey bee castes, lasting only 15-16 days. An egg is an egg for 3 days, then hatches into a larva. A larva that will develop into a queen is fed only royal jelly by the nurse bees and is a larva for 6 days. On the 9th day, the cell of a queen, much larger than that of a worker or drone (looks like a peanut hanging off the side or bottom of the frame), is capped. Inside the capped cell, the queen pupates rapidly, emerging (eclosing) from the cell as an adult on day 15 or 16. Cells of queens that have successfully emerged have little, round hatches at the bottom of the cell. Cells of queens that have been killed by other, faster eclosing queens or that have not successfully developed and whose cells were dismantled by the worker bees have oblong holes on the side of the cell. Closure (E-) Right after eclosure, a queen is what is called a virgin queen. She has not mated with any drones and therefore cannot lay fertilized eggs. Before she can go on one or more mating flights, however, she must orientate herself in the hive for about a week and allow her reproductive organs to mature. Her mating flights will be taken in the next 1-2 weeks (weather depending), and then she will typically require close to an additional week to start laying fertilized eggs. All up, from the time a queen ecloses to when she lays her first egg can be up to a month! That doesn’t include the just over 2 weeks from egg to eclosure. Patience is key when allowing a hive to make a new queen from an egg or young larva. More Information: https://extension.psu.edu/an-introduction-to-queen-honey-bee-development

3 Comments

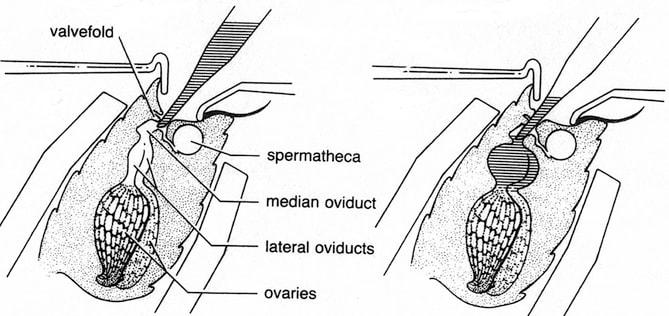

Artificial Insemination Diagram Honey Bee, Credit J. Harbo USDA Artificial Insemination Diagram Honey Bee, Credit J. Harbo USDA Assortment In the last post we discussed the different subspecies of Apis mellifera, the Western honey bee, the species of honey bee kept by beekeepers in the United States. From these subspecies, people have bred certain strains or stocks of bees. This selective breeding is usually done to preserve certain desirable traits, usually disease or mite resistance. The definitions of strains, stock, lines, and breeds of bees is a little murky and sometimes purebred subspecies of A. mellifera are also referred to as strains, stocks, lines, or breeds. Buckfast Some common honey bee stocks include: Buckfast, Saskatraz, Purdue Ankle-Biter (PAB), Varroa Sensitive Hygienic (VSH), feral chewers, and “survivor stock.” The Buckfast bee line is a subspecies of A. mellifera (A. m. buckfast) and was developed by a monk in England to fight the devastation wrought on English bees in the early 1900s by the tracheal mite. These are a combination of Italian bees and German bees. Saskatraz bees are from a breeding program in Saskatchewan, Canada whose primary goal was increased honey production (anecdotal reports say they are also resistant to Varroa mites). All the rest of the mentioned strains have been bred for either general disease (VSH) or Varroa mite resistance. “Survivor stock” are from overwintered colonies who survived Varroa mites with only rigorous IPM mite management and no chemical treatments. PABs and feral chewers are known for their increased grooming habits which include chewing the legs off of the adult mites and killing them. Control It is difficult to selectively breed bees because the queens mate away from the hive with 10-20 different drones from multiple colonies that are not their own. This maintains the genetic diversity which is normally better for keeping a colony healthy and prevents inbreeding. Unfortunately, this also means that most beekeepers have no control over the genetics their queens return with after a mating flight. Selective breeding programs either artificially inseminate the queens with sperm from drones with the desired genetic trait, or supersaturate the miles surrounding the queen’s hive with drones with the desired genetic trait. More Information: https://honeybeehealthcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Commercial_Beekeeping_062121.pdf (page 3)  Giant Honey Bees Giant Honey Bees Apis There are between 7 and 11 different species of honey bees. For example, Apis cerana, the Eastern or Asian honey bee is the original host for the Varroa mite, but is not found in North America. Apis dorsata, the giant honey bee, is also only found in South and Southeast Asia. Apis koschevnikovi inhabits Malaysian and Indonesian Borneo. Again, there are no native honey bees in North America, but the colonists brought over Apis mellifera, Western honey bees, and they have been present in North America ever since. Breeds Within the species Apis mellifera, there are 26 recognized subspecies. The most widely known subspecies is Apis mellifera scutellata, better known as the “Africanized” honey bee. Other common European subspecies of Apis mellifera include: Apis mellifera ligustica (Italian honey bee), A. mellifera carnica (Carniolan honey bee), A. m. mellifera (German black bee), A. m. caucasia (Caucasian honey bee), and A. m. artemisia (Russian honey bee). Characteristics Many bees in North America have become hybrids of these subspecies, so bees not obtained from a certified breeder will probably have mixed genetics from more than one of these subspecies. Generally, overwintered MI bees are considered “Michigan mutts.” However, some beekeepers choose to start with or maintain more pure lines of bees or hybrid bees that are a cross between certain subspecies based on the traits of those subspecies. For example, many people prefer Italians because of their calm temperament and increased honey production. Others prefer Russian bees for their reported Varroa mite resistance. Most beekeepers in the U.S. try to avoid keeping bees with Apis mellifera scutellata genetics because they tend to be super defensive bordering on aggressive, sting more frequently, swarm more often, and produce little honey. However, they are routinely kept by African beekeepers. More Information: https://bee-health.extension.org/subspecies-the-place-of-honey-bees-in-the-world/  America Many people get into beekeeping to “save the bees,” and honey bees have become a vital part of our agricultural system, pollinating crops such as almonds, blueberries, and apples. Unfortunately, honey bees are not native to North America, so keeping honey bees to “save the bees” is a lot like keeping backyard chickens to help with the plight of the Kirtland’s Warbler. Worse, when uneducated beekeepers fail to manage their colonies properly, they spread pests and diseases to our native bees, doing harm instead of good. But… I am NOT saying that we shouldn’t keep honey bees. I enjoy keeping bees, love honey, and have no intention of giving that up. However, what I am saying is that there are much better things to do to “save the bees” than to become a beekeeper. These include, but aren’t limited to, planting native forage, never planting ornamental flowers, limiting or stopping the use of pesticides in your yard, encouraging your local government to plant community gardens of native plants, cutting down on the amount of lawn you have and replacing it with native plants, supporting bee-friendly farms, planting bee-friendly trees, and donating to organizations who support pollinator education and conservation. Consider Consider also that honey bees often compete with native bees for our dwindling floral resources. Since the 1930s, the United States has lost a staggering 97% of wildflower meadows, leaving little forage for our native bees. Additionally, honey bees are often attracted to invasive plant species such as star thistle, proliferating this noxious weed. More Information: https://www.nwf.org/Home/Magazines/National-Wildlife/2021/June-July/Gardening/Honey-Bees  Apis mellifera Apis mellifera is the western honey bee. Its native range is Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. It is one of the only eusocial animal species on the planet, meaning that a colony of honey bees is a superorganism. No one individual bee can survive on its own. Bees There are over 16,000 species of bees in the world, about 4,000 of which are native to North America, and around 450 species of which are native to Michigan. Of those 16,000+ species, only around 8 species of bees produce honey. There are no native honey-producing bees in North America. Most bees are solitary bees and do not live in colonies. Castes Being a eusocial superorganism means that honey bees are divided into castes or physiologically different variations of the same species. The 3 honey bee castes are the queen, workers, and drones. The queen is the only fertile female in the colony and lays all the eggs. She is the largest bee in the hive. The workers are all sterile females who, as their name suggests, do all of the work inside and outside the hive including brood rearing, foraging for food, wax building, taking care of the queen, and many, many other tasks. The drones are the male bees. They are larger than the workers and their only job is to fertilize virgin queen bees. More Information: https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Invertebrates/Bees |

AuthorJen Haeger is a new master beekeeper and board member of A2B2. Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed