https://beeaware.org.au https://beeaware.org.au Ailment A big thing to watch for in the spring is signs of disease in your hives. Cool, wet springs often bring brood diseases such as sacbrood, chalkbrood, Nosema/dysentery, and European foulbrood (EFB). Sacbrood is a viral disease where the larvae turn brown and pointy. Chalkbrood is a fungal disease where the larvae look like black, white, or gray mummies. Nosema apis is a microsporidian parasite that can cause dysentery (diarrhea) in bees that can be seen as tan to brown streaks on the tops of the frames and around the hive entrance. Bees can also get dysentery from too much ash in their diet or too much moisture in their hive. EFB is a bacterial disease that causes the larvae to look yellow, twisted, and “skeletal.” Treatment of these spring diseases includes feeding sugar syrup, taking care of moisture problems in the hive, and sometimes requeening the hive. Varroa testing and treatment should also begin in the spring. Backfilling In the early spring before many plants are blooming, beekeepers may also want to feed their colonies. Feeding pollen, the bee’s source of protein, can encourage your queen to lay more eggs. You may also want to feed 1:1 sugar syrup to encourage comb production if you have undrawn foundation frames. Sometimes feeding too much sugar syrup may induce a swarm if the bees choose to store the syrup in the brood chamber (called backfilling) and the queen runs out of space to lay her eggs. Copy Spring is the time of year where honey bees, like most animals, reproduce. Though the queen lays eggs throughout most of the year to replenish and boost the population of the colony, the true, natural reproduction of the honey bee colony is a swarm. If you hive survived the winter, has a laying queen, and has pollen coming in, you will need to watch for signs that your colony may be ready to swarm. Since swarming causes the loss of bees and introduces a non-native species into the environment, beekeepers try to prevent swarms either by giving their bees more drawn comb or by splitting their colonies. Another technique that may be useful in the spring is called reversing. This is moving an empty box of frames from the bottom of the hive to the top. The bottom box may be empty (no bees) because the bees move up to the top of the hive during the winter. This is also a good time to replace frames of old, dark comb from the empty box with fresh foundation frames. More Information: https://pollinator.cals.cornell.edu/sites/pollinator.cals.cornell.edu/files/shared/documents/Beekeeping%20Calendar%20for%20the%20Northeast.pdf

0 Comments

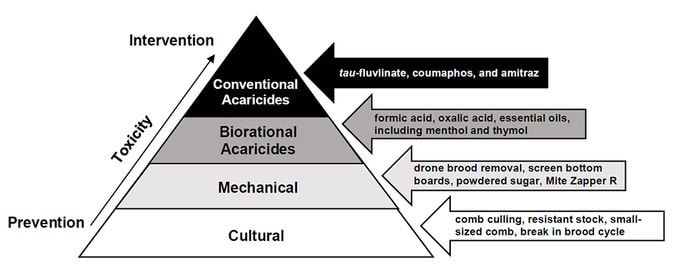

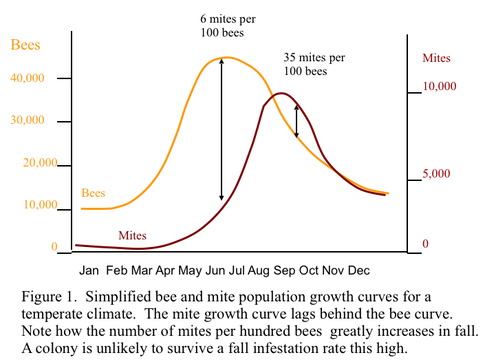

American Foulbrood rope test (Vita Bee Health) American Foulbrood rope test (Vita Bee Health) AFB American Foulbrood or AFB is a serious, highly contagious, and fatal bacterial disease in honey bees. It does not affect humans. The bacteria, Paenibacillus larvae, is fed to the bee brood as a spore from contaminated honey and then turns vegetative (reproductive) in the gut of the bee larva. This disease effects the bee brood typically after it has been capped, and instead of developing into a pupa and eventually an adult under the wax cap, the larva turns into a mass of bacterial goo containing millions to billions of spores. Less than 10 spores are needed to cause infection in a new larva. Burn Because this disease is so serious and contagious, infected hives must be quarantined and no equipment shared with any other hives. Though able to be controlled with antibiotics, the recommended treatment for a small operation is closing up the affected hive at night, digging a hole, placing the whole hive in the hole, burning it, and then burying the ashes. Some states REQUIRE you to do this. It may seem extreme, but the spores of AFB remain infectious for more than 80 years and are not destroyed through any common sterilization techniques. AFB is the main reason new beekeepers should not purchase old equipment, especially frames, from sources such as Craig’s List. Caramel Signs of AFB include a spotty brood pattern, caramel colored brood, sunken wax cappings often with holes in them, near black scales in brood cells that are impossible to remove, snotty/ropey larval goo, a foul or rotting smell, and a structure called a pupal tongue in brood cells (a thin, dark, pointy structure crossing the cell). While some of these signs can be seen with other brood diseases, the hard, black scales, larval goo ropes of at least 3.5cm, and pupal tongues are only seen with AFB. There are three tests for AFB: 1) Commercial Kit (similar to a COVID or pregnancy test), 2) Match Stick/Rope Test, 3) Holst Milk Test. More Information: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=caliX8JZJ2s  Image modified by Morgan Roth, based on source material from the State of Hawaii Plant Industry Division Image modified by Morgan Roth, based on source material from the State of Hawaii Plant Industry Division Acids (& oils) The next level of the IPM pyramid is where intervention/treatment begins with what are termed “soft” chemicals. These are naturally occurring acids and essential oils commercially formulated for maximum efficacy against Varroa mites with minimal harm to your bees. “Soft” chemical acids include HopGuard 3, FormicPro, MiteAway Quick Strips, and Oxalic Acid. “Soft” essential oil treatments include formulations containing menthol and thymol like ApiLife Var. At the top of the pyramid are “hard” chemicals or conventional pesticides, to which Varroa mites have already developed resistance in some cases. These include amitraz (Taktic, Apivar), tau-fluvlinate, and coumaphos. Beware Any chemical treatment needs to be used with the utmost care with thought given to the temperature, time of year, whether or not honey supers are present, if there is brood present in the hive, and what protection needs to be worn by the beekeeper when administering the treatment. It is illegal to apply chemical treatments to your hive in a manner inconsistent with the instruction label. It is illegal to apply pesticides (including essential oils) to your hives that have not been approved for use as Varroa mite treatment in honey bees. When treating, it is best to treat all hives in an apiary at the same time. This prevents the mites from "hive-hopping" from the treated hive to an untreated hive. Cruel Do you know what doesn’t work as a treatment? Doing nothing, letting your bees “develop resistance” against Varroa, letting the “weak” bees die (this is animal cruelty), and creating Varroa bombs that infect your neighbor’s hives and the local native bee population. “Treatment-free” does not mean doing nothing. In fact, it is a rigorous system of integrated pest management that includes actively euthanizing mite-susceptible hives. For most new beekeepers, this is not a viable strategy for mite control. More Information: https://honeybeehealthcoalition.org/varroatool/  Alcohol The first step to integrated pest management of Varroa mites is testing your hives about once a month to monitor your mite levels so that you can treat at the appropriate time with the appropriate treatment. There are 2 validated testing methods for Varroa mites: 1) the powdered sugar roll, and 2) the alcohol wash. Of the two, the alcohol wash is easier and more accurate, but it does kill the tested bees (although properly done, the powdered sugar roll will also probably kill some bees). Both tests require 300 bees (½ a cup) collected from the brood chamber. Sticky boards are often advertised as a non-invasive way to test for Varroa mites, but these are not an accurate or useful way to test your mite levels. Testing is crucial to mite control because treating at the wrong time can be harmful to your bees and create resistance in the mites. There is an app called MiteCheck to help guide you in testing your bees for Varroa mites. Biters Think of IPM as a pyramid. At the bottom are preventative techniques and at the top are interventions/treatments. The base of preventative techniques is termed cultural. These include culling old comb (Varroa prefer old comb), introducing mite-resistant bee stock into your apiary such as Purdue Ankle-Biters, VSH (Varroa Sensitive Hygienic) or Saskatraz, and breaking the brood cycle (because the mites reproduce in the brood). Some models will also list small-cell comb as a cultural control, but recent studies have proven this is not an effective control of Varroa mites. Capture Next are physical or mechanical techniques. These include drone board removal or drone-trapping (which physically removes mites from the hive), screened bottom boards (which may prevent mites groomed from adult bees from crawling back on bees), and new products which heat the hives to temperatures at which mites cannot live. Some models will also list powdered sugar as a physical control of Varroa mites, but scientific studies have shown that the periodic application of powdered sugar by sprinkling it into hives is ineffective in controlling Varroa mites. More Information: https://pollinator.cals.cornell.edu/sites/pollinator.cals.cornell.edu/files/shared/documents/2020%20IPM%20for%20Varroa%20Mite%20Control.pdf  Copyright Randy Oliver, Scientific Beekeeping, 2006 Copyright Randy Oliver, Scientific Beekeeping, 2006 Accelerated Varroa mites breed exponentially. This means that an untreated, unmanaged hive with one mite in the spring will have thousands of mites by the fall. To make matters worse, the mite population of the hive is peaking just as the adult bee population of the hive is dwindling and just as special winter bees are being made to try to ensure the survival of the hive through the winter. The physical and physiological damage that the mites cause means that even if the hive technically survives to winter, the winter bees of the infected hive will likely be small and weaker than those of a healthy hive and the colony will not survive the winter. Booming One thing that sounds counterintuitive when it comes to Varroa mites is that big, booming colonies are more affected by mites than smaller, weaker colonies. This is because the mites breed inside the brood and a large hive with tons of brood will also therefore have a much higher mite load. Smaller colonies don’t have as much brood for the mites to “hide” in and breed in, and adult mites on adult bees may be groomed off by other bees. Unfortunately for beekeepers, it is often their largest, most “successful” hives that succumb to Varroa mites. Capped Varroa mites reproduce inside the capped brood cells of honey bees. The adult females can sense when a cell is about to be capped and jump into the cell and hide under the bee larva until the cell is capped. When the larva begins to pupate, the foundress mite feeds on the pupa and begins to lay her eggs. The first egg is always a male and the subsequent eggs are all females. When the eggs hatch the female mites will breed with the male mite and when the weakened adult bee emerges from the cell, the mated females (including the foundress) will escape and find adult bees to attach to. Varroa mites prefer to reproduce in drone brood cells because drones take longer to mature and therefore more of the mite eggs will have time to hatch and mate releasing more mature, adult mites on average. More Information: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k6y9FqNw6y8  All All honey bee colonies, except those which are extremely isolated with no other hives in at least a 12-mile radius, are affected by Varroa mites or subject to infection through visiting the same flowers as infected bees, robbing hives infected by Varroa, “drift” (bees coming home to the wrong hive) of bees from infected hives, and most importantly from hives that have become “Varroa bombs.” A Varroa bomb is a colony that has become so infested with Varroa mites, that the remaining live bees all abscond (leave in mass) from the hive and fly off in every direction to find a new hive. These bees spread the mite infection far and wide and can cause a rapid and fatal increase in Varroa mites, even in a previously uninfected hive. Big Beekeeping in North America is now much more difficult due to this insidious parasite. Large for mite, Varroa is still nearly impossible to spot on a honey bee because it often hides between the plates of exoskeleton on the bee’s abdomen where it punches a hole in the bee’s cuticle and feeds on the adult bee’s fat bodies. Varroa also damages bee pupae when it reproduces inside capped brood cells and feeds off the developing brood. As if this was not enough damage, Varroa mites have also been shown to spread bee viruses such as Deformed Wing Virus (DWV) and activate bee viruses already present in a colony. Cerana In 1985 beekeeping in North America was forever changed by the introduction of the Varroa destructor mite from Asia where it is a parasite of the Asian honey bee, Apis cerana. Apis cerana, having evolved alongside the Varroa mite, has developed multiple strategies for dealing with it. Unfortunately, Apis mellifera, the Western honey bee and the bee kept by almost all beekeepers in North America, did not evolve with this mite, and has had little time to adapt to Varroa destructor. More Information: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0135103 |

AuthorJen Haeger is a new master beekeeper and board member of A2B2. Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed